by Christina Lengyel

Lead paint, coal furnaces, hallway instruction, classrooms partitioned with teetering stacks of books and supplies, students and teachers struggling to work in unabated heat during sweltering weather — these are all images invoked by testifiers before the Basic Education Funding Commission over the last few months.

Experts say this barely scratches the surface of a massive infrastructural crisis across the state.

“The BEFC must identify the steps needed for ensuring our public schools will, in the very near future, give every child the public education they are entitled to in the facilities they deserve without leaving the burden to local taxpayers,” said Lynn Fuini-Hetten, Superintendent of Salisbury Township School District, in her testimony September 12th.

Students like Fatouma Sidibe, who spoke before the commission in Lancaster on September 21, demonstrated the goodwill lost between children and the adults charged with their care when school environments reflect what many say is the de-prioritization of students, especially those of color.

“We’re required to invest so much time with little effort given back to us with support for our success. We don’t even have a library, or a cafeteria,” Sidibe said. “Two bare minimum things that kids need to get through the day. We shouldn’t have to go through so much just to get an underfunded education.”

Similar conditions face children who aren’t old enough to speak for themselves, said Brian Costello, superintendent of the Wilkes-Barre Area School District, regarding Kistler Elementary.

“Several rooms are divided in half with whiteboards and bookcases to accommodate multiple classes, and students who need occupational therapy receive it in a makeshift room that was once a storage closet,” he said.

Districts across the state in all types of communities are suffering with aging buildings with outdated equipment that fail to meet today’s health, safety, accessibility, and pedagogical demands.

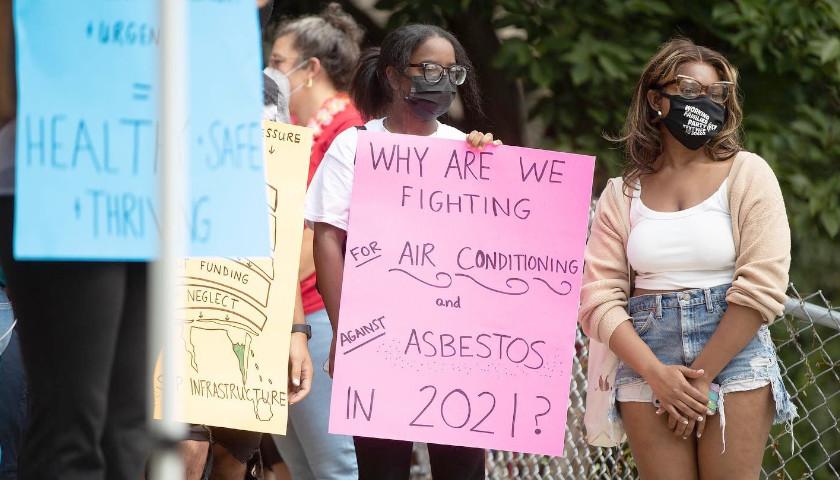

From carcinogenic asbestos exposure to lead poisoning, teachers and students are grappling with facilities that have a very real risk of making them sick.

“Philadelphia is a city with a lead problem worse than the infamous issues in Flint, so it is important we address lead and other toxic conditions in our schools and communities immediately,” said Sen. Vincent Hughes, D-Philadelphia.

Climate control is a major issue, causing schools across the commonwealth to cancel classes when temperatures rise.

Jerry T. Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, lamented students “learning in buildings so old and with such deferred maintenance that their electrical systems could not even handle air conditioning units even if they were provided.”

Lancaster teacher Brenda Morales reiterated the challenges in her testimony a week later.

“You can’t imagine how miserable it is to work in extreme heat or cold. I used to keep a pile of sweatshirts for days when the boiler system was acting up, but there wasn’t anything I could do on super-hot days,” she said. “Studies have found that extreme temperatures impact a student’s (and teacher’s) ability to focus.”

Meanwhile in the age of mass shootings, many facilities are not living up to the standards required to keep children safe – such as unsecured entrance vestibules, exterior doors that don’t lock when closed and interior classroom doors that can only be locked from the hallway.

The cost burden of infrastructure needs around the state seems almost insurmountable, with Committee Chairman Mike Sturla, D-Lancaster, said schools need roughly $2.5 billion every year for at least 100 years to bring the situation up to snuff.

In Philadelphia alone, one of the largest school districts in the entire country, the average building age is 73 years, and the district’s deferred maintenance cost is $4.5 billion. Eighty-five buildings require renovation and 21 should be considered for closure, according to Reginald L. Streater, the Board of Education President for the district.

Experts say there is hope to be had for finding an approach to correcting this situation. Michael Kelly – who noted that little had changed since he spoke to Congress about facilities in 2017 – urged the commission to fund PlanCon, a program passed into law in 2019 that provides a process and formula for schools to assess their needs and generate the appropriate funding from the state for a long-term plan of action.

As many testifiers have mentioned regarding a wide range of issues, Kelly emphasized the need for predictable long-term funding. Year after year, administrators wait for last-minute budgets from the state to determine what decisions they’ll be able to make, an untenable situation, especially for those schools in more highly populated and less wealthy districts that aren’t able to rely heavily on proceeds from local property tax.

– – –

Christina Lengyel is a contributor to The Center Square.

Photo “Pennsylvania Public School Infrastructure Protest” by State Senator Vincent Hughes.